PART 1: Lifetimes In Rust

Jul 09 2024

5 min read

2K

“Rust Lifetimes: The Magical Memory Safety Trick You Won’t Find in Other Languages!”

Lifetime!

Over the past several months, I have dedicated myself to learning and understanding Rust, a language that has captured the interest of many software engineers. Starting with simple applications and progressing to more interesting projects, such as developing a basic HTTP server, I have been consistently impressed by Rust’s unique features and its distinctive approach compared to other low-level languages.

This article is the first part of my upcoming series titled “Understanding Rust with Me,” where I will share some of the intriguing aspects of Rust that I have discovered. In this pilot article, I will focus on ‘Lifetimes,’ a concept I have chosen to explore in depth. I aim to provide a detailed explanation of Rust's lifetimes, sharing my insights while also deepening my understanding of this remarkable feature. Now let’s begin!!!

Different programming languages handle memory safety in various ways. Low-level languages like C and C++ give developers the power to allocate and deallocate memory manually. While this control is powerful, it comes with significant risks. Without careful management, developers can introduce issues like memory leaks, dangling pointers, or buffer overflows. These problems can result in unsafe applications, as the compiler will compile the code without catching these errors, leading to potential runtime issues.

Higher-level languages like Python, JavaScript, and Go use garbage collection to manage memory automatically. A garbage collector identifies and frees up memory used by variables that are no longer needed (i.e., variables with no remaining references). This process abstracts the task of memory management from developers, preventing memory leaks and making programming easier and safer. However, it can occasionally slow down applications due to the pauses required for garbage collection.

Rust’s Unique Approach to Memory Safety

Rust offers a unique solution by combining the safety of garbage collection with the performance and control of manual memory management.

Rust ensures memory safety without the need for a garbage collector by using an ownership and lifetime system. This system tracks how long variables are in use and enforces strict rules to prevent common memory errors. Unlike other low-level languages that might compile code with hidden memory leaks or dangling pointers, Rust catches these errors at compile time. This approach allows Rust to combine the efficiency and control of low-level languages with the safety typically found in higher-level languages.

What are Lifetimes?

LIFETIMES — in simple terms, Lifetimes is a way to describe how long references (pointers to data) are valid. They help ensure that references do not outlive the data they point to, preventing “dangling references” (see above for meaning).

To make this clearer, let’s consider a scenario: Imagine you have a piece of data (like a variable), and you create a reference to that data. If the data is deleted or goes out of scope (meaning it’s no longer valid), but your reference still exists and tries to access the data, this would lead to errors or unexpected behavior in many low-level languages. However, Rust uses lifetimes to ensure that references are always valid while they are being used. If Rust finds any reference that isn’t valid, it returns an error at compile time, preventing these issues before the code even runs.

Lifetimes in Rust are annotated using an apostrophe (') followed by a name.

Understanding Borrowing and the Borrow Checker

Before continuing and demonstrating how to write a function that utilizes lifetimes, it’s important to understand that lifetimes and the borrow checker work together. Borrowing is another crucial feature in Rust, which we will explore in depth in a future article. Rust is generally able to infer lifetimes, except in more complex functions or in a function that accepts references as parameters or returns a reference in this case the Rust compiler needs explicit lifetime annotations

Example: Rust Inferring Lifetimes

Take a look at the below code and see how Rust can infer lifetimes, once the borrow checker is happy 😊

In this example:

- The compiler infers that the lifetime of r is the same as the lifetime of x, as they are in the same scope.

- The borrow checker verifies that r is only used while x is valid, preventing any dangling references.

Enforcing Borrowing Rules

An example of borrow checker enforcing 1 of the 3 Rust’s strict borrowing rules —

When the compiler analyzes the above code, it sees that r is trying to reference x after x has already been dropped. This leads to a compile-time error:

Explicit Lifetime Annotations

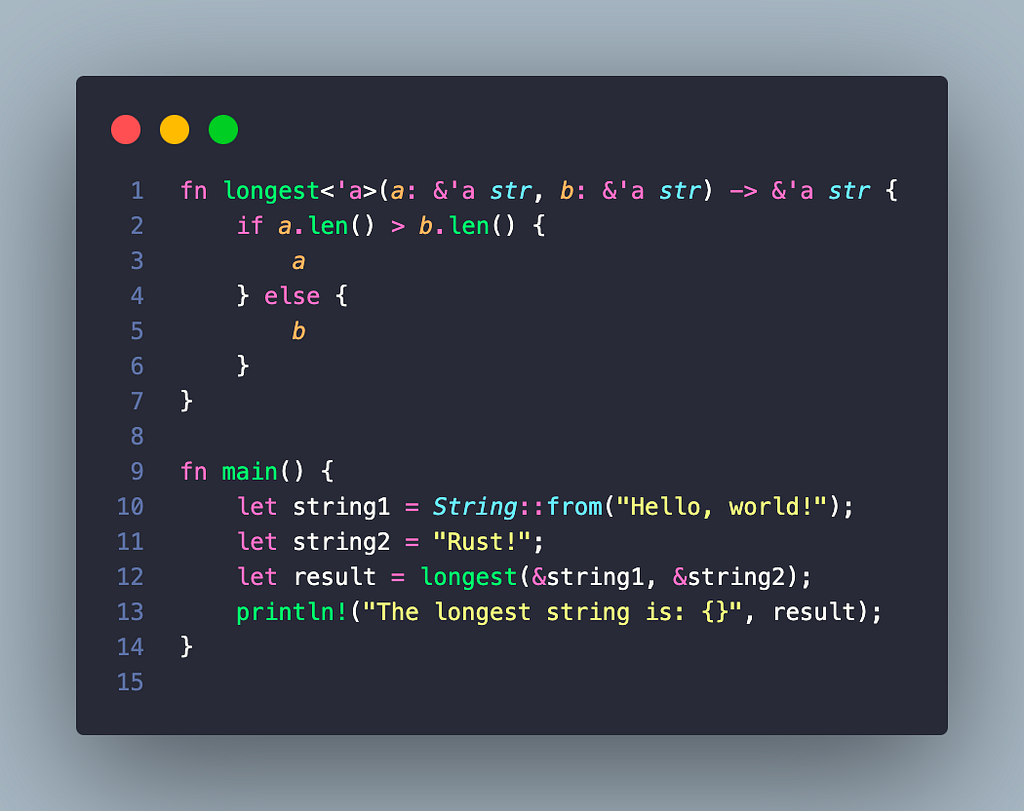

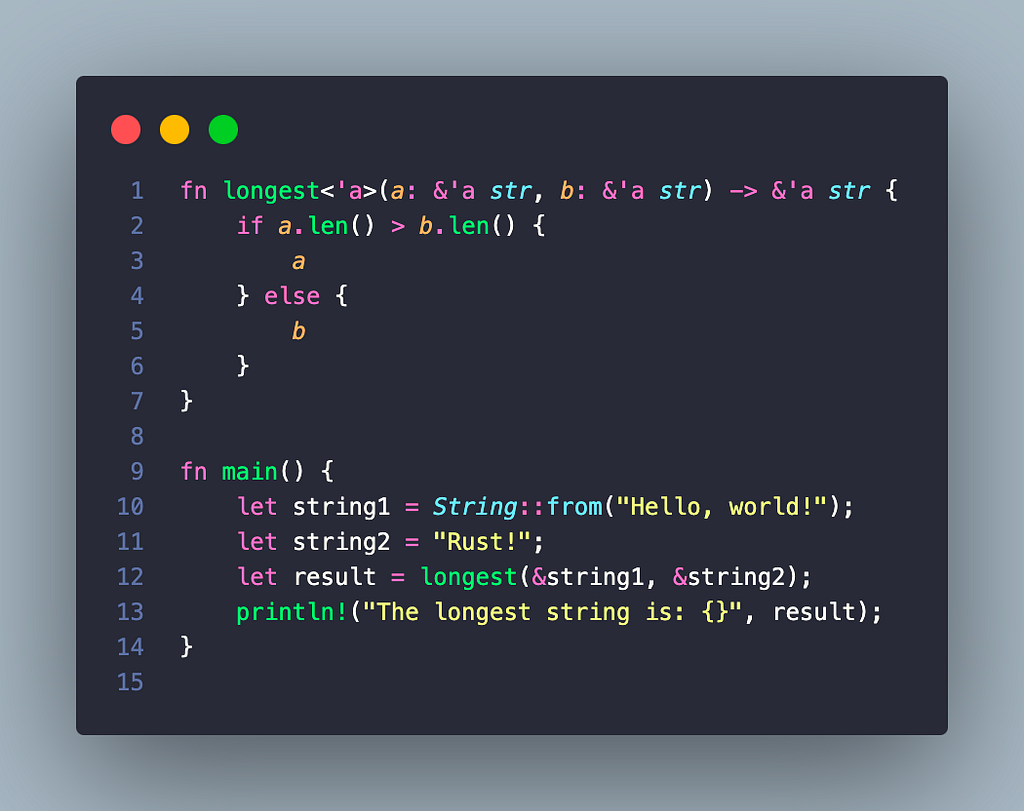

A scenario where you will need to explicitly infer lifetimes:

The example function above will not compile because the compiler cannot infer the lifetimes of the references to ensure they are valid.

Fixing with Lifetime Annotations

Looking at the above example you are probably wondering, “why can’t the compiler infer lifetimes for the longest function implicitly if it knows the lifetime of the main function and they are all in the same scope?”. Like we have discussed earlier Rust compiler is able to infer simple references, the Ellison Rule is what it uses to see if lifetimes can be inferred.

Lifetime Elision Rules

These rules help the compiler infer lifetimes in simple and common cases without requiring explicit annotations. However, they are limited in scope. Here’s how these rules work:

- Each reference parameter gets its own lifetime parameter.

- If there is exactly one input lifetime, that lifetime is assigned to all output lifetimes.

- If there are multiple input lifetimes, but one of them is &self or &mut self, the lifetime of self is assigned to all output lifetimes.

In the code above, the function longest has two input lifetimes ('a and 'b), and the compiler needs to know that the output lifetime is tied to both of these input lifetimes. The rules are not enough to infer this relationship because there are multiple input lifetimes and neither of them is self.

Summary

Rust’s lifetime system is a powerful feature that ensures memory safety without the need for a garbage collector. By understanding and using lifetimes, you can write more efficient and error-free code. This article introduced the basics of lifetimes, and in future articles, we will delve deeper into borrowing, ownership, and more advanced lifetime usage scenarios. Stay tuned for more insights into Rust’s remarkable features!